In November 2022, the United Nations estimated that Earth’s population had reached 8 billion people. These figures are always approximations, but they highlight a key trend: By 2023, humanity was no longer reaching the replacement rate, and population growth is expected to peak by the end of the century before declining irreversibly.

How accurate are these numbers? A new study suggests that global population estimates may be significantly off, with hundreds of millions—possibly even billions—of people missing from official counts.

Can we trust the numbers? The 2024 World Population Prospects study states, “Population trends are highly uncertain, especially in the long run.” While scientific methods aim for accuracy, the study underscores that uncertainty is the only certainty when predicting population numbers.

That doesn’t mean demographers fabricate the numbers. Since 1950, they’ve used national data and trends to make predictions, but what if that data isn’t entirely reliable?

Millions—or billions—are missing. A new study published in Nature by researchers at Aalto University in Finland suggests that the datasets demographers use “profoundly and systematically” underestimate the global population. And the numbers are staggering—potentially between 1 and 3 billion people have been left out.

Examples of tools demographers use in their analyses, each reflecting a different bias.

Examples of tools demographers use in their analyses, each reflecting a different bias.

Rural populations. Josias Láng-Ritter, one of the study’s lead researchers, points to a key issue: undercounting rural populations. “For the first time, our study provides evidence that a significant proportion of the rural population may be missing from global population datasets,” he explains.

The expert isn’t talking about just a few million people—according to the study, rural populations have been underestimated by 53% to 84% over the period analyzed. “The results are remarkable, as these datasets have been used in thousands of studies and extensively support decision-making, yet their accuracy has not been systematically evaluated,” Láng-Ritter adds.

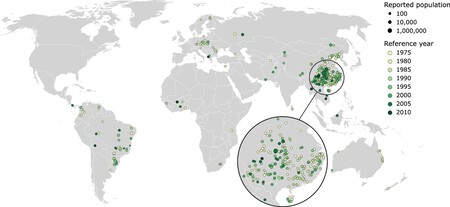

The map highlights the 307 rural areas researchers analyzed in the study, revealing that reported populations were underestimated by 53% to 84%.

The map highlights the 307 rural areas researchers analyzed in the study, revealing that reported populations were underestimated by 53% to 84%.

Biases. Attempts to verify population estimates aren’t new, but past studies mostly focused on urban areas or specific countries. The Aalto University team took a different approach: They compared the five most widely used global population datasets and cross-referenced them with high-resolution population maps. Their method involved analyzing resettlement data from over 300 rural dam projects across 35 countries.

Why focus on dams? When a government builds a dam, it has to relocate people living in the affected area. These resettlements are well-documented, making them an ideal benchmark for measuring population accuracy. By comparing actual resettlement numbers from 1975 to 2010 with population estimates from the same period, the researchers found that while estimates improved over time, the 2010 maps still omitted between 32% and 77% of the rural population.

Even with dataset updates between 2015 and 2020, demographers believe that rural undercounting remains a widespread issue across all world regions.

Average percentage of the rural population underestimated (red and orange) or overestimated (blue).

Average percentage of the rural population underestimated (red and orange) or overestimated (blue).

Why it matters. Fixing this issue isn’t easy. Governments often lack the resources to accurately count people in remote rural regions. As a result, the discrepancy between actual population numbers and demographic estimates can significantly impact policy decisions. This has real-world consequences.

Current estimates suggest that 43% of the world’s 8.2 billion people live in rural areas—about 3.526 billion people. If rural populations are underestimated by even 53%, then at least 1.8 billion people are missing from official counts. If the underestimation reaches 84%, that number jumps to nearly 3 billion.

The impact of inaccurate data. Without accurate population data, governments and organizations struggle to allocate resources effectively. Láng-Ritter offers an example:

“In many countries, there may not be sufficient data available on a national level, so they rely on global population maps to support their decision-making: Do we need an asphalted road or a hospital? How much medicine is required in a particular area? How many people could be affected by natural disasters such as earthquakes or floods?”

A striking case is Paraguay, where the 2012 census may have overlooked a quarter of the population.

A call for better methods. The study found that some countries handle population data better than others. Finland, for example, has reliable population records thanks to its early adoption of digital census tracking 30 years ago. In contrast, countries that have faced crises or delays in digital record-keeping often show large discrepancies between actual and estimated populations.

“To provide rural communities with equal access to services and other resources, we need to have a critical discussion about the past and future applications of these population maps,” Láng-Ritter emphasizes. According to the expert, governments must base their social policies on solid evidence—not just rough estimates.

Image | Ryoji Iwata (Unsplash)

Related | Japan’s Aging Population Hits Rock Bottom: More Older Adults Are Choosing to Live in Prison

Log in to leave a comment